Long Read

The rise and fall of the Oligarch-maker

How one mysterious financier came to sit at the top table of oligarchs and power.

17 Aug 2021 | 26 min read

By Adrian Gatton

He had glittering success – a long career managing one of the world’s biggest trust companies and making millions from Russia’s oligarchs. Even as his clients mysteriously died, one by one, he managed to stay in the shadows and remain ahead of the game.

Until undercover reporters from Al Jazeera’s I-Unit caught him on secret camera agreeing to sell an English football club to a convicted Chinese criminal, in breach of football regulations.

Who was this man? And how deep did his business connections go?

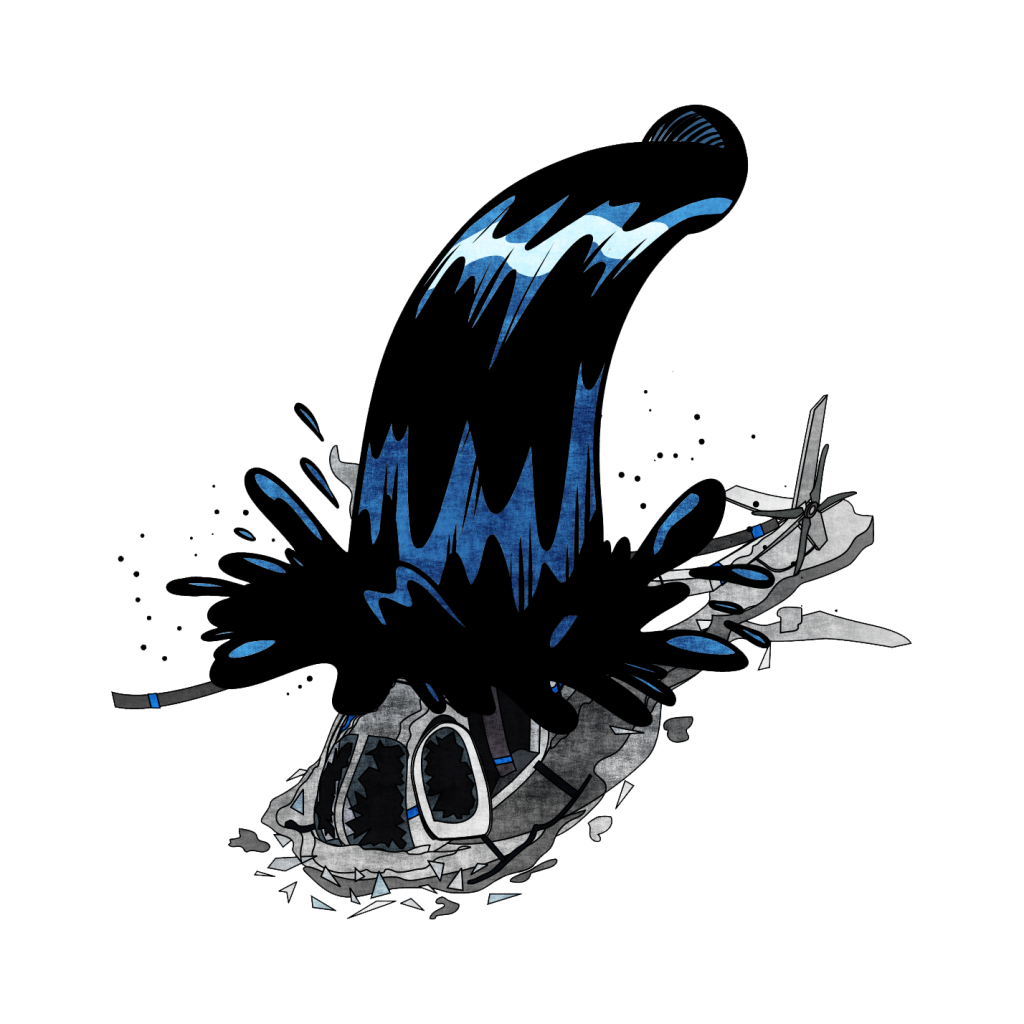

A helicopter falls from the sky

At 7:41pm on a spring evening in 2004, an Augusta 109E helicopter cratered into a field in rural Dorset, southern England, two tonnes of steel, wiring and fuel exploding into a fireball.

Nick Kenchington started at the roar of rotor blades above his cottage, fearing the helicopter would “take the roof off”.

“The helicopter flew very low and drowned out the TV,” he later said. His wife got up and opened the curtains. “Then, I saw a white flash in the sky,” Kenchington said. “A second later, we heard a bang. You could see flames all over the meadow below.”

The pilot and his single passenger – lawyer Stephen Curtis – had died in the flames after the helicopter nose-dived into the field, according to air accident investigators.

Curtis had faced threats in the weeks before the crash. Private investigators told him his telephones were tapped. His bodyguards found a bug at his house, according to reports. A message was left on his phone: “Curtis, where are you? We are here. We are behind you. We follow you.”

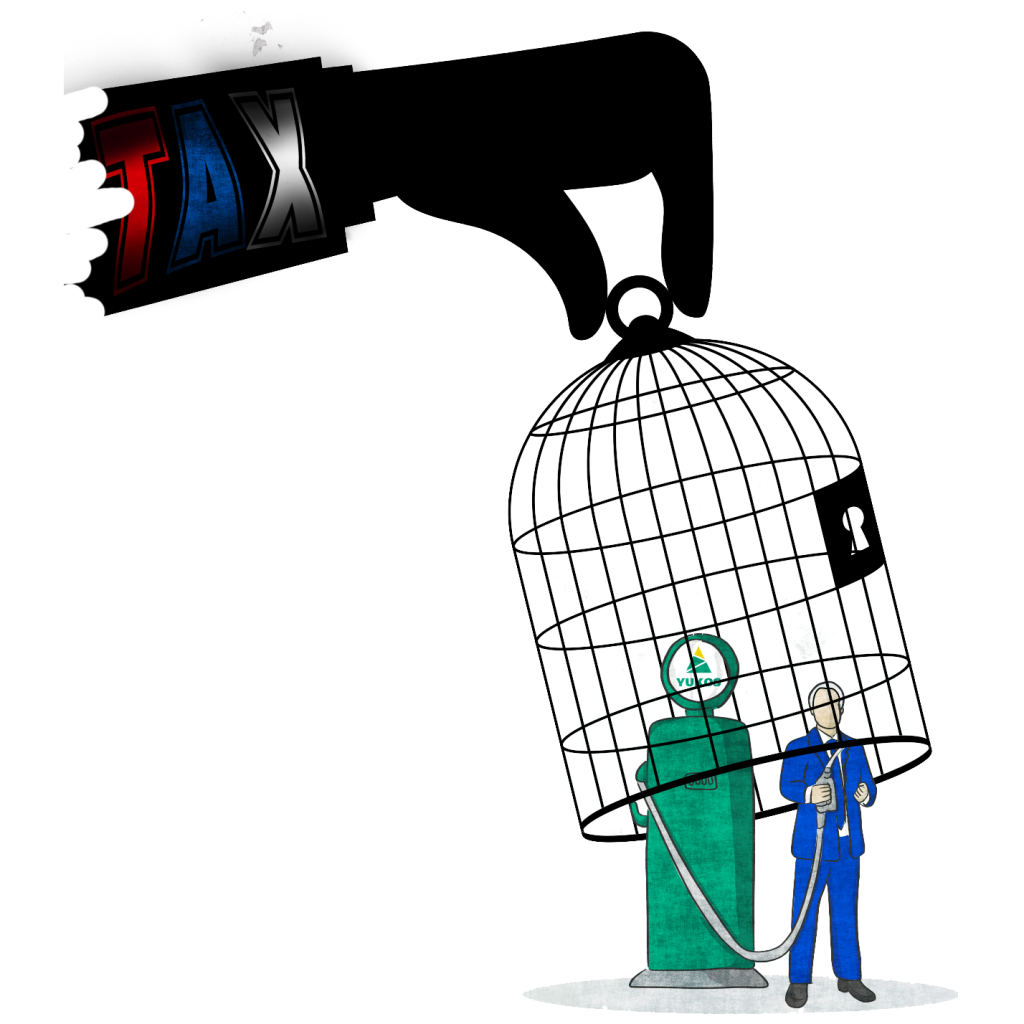

He was an obscure English lawyer with a remarkable job, running Menatep, a company that controlled Russia’s biggest oil company, Yukos.

Yukos was in conflict with the Russian government, allegedly over unpaid taxes. But it was more than that: it was about the political threat posed by Yukos’ chief, oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, to spymaster-turned-President Vladimir Putin. Powerful adversaries locked in a battle of wills.

In a twist that would emerge in the weeks after his death, Curtis had approached the National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS) – the British police-intelligence liaison agency – and offered to serve as an informant. Days before his fatal flight from a London heliport, he had met an agency handler. The morning after his death, Swiss police raided Yukos-related entities in the country; $5bn in assets was frozen.

“The timing could not have been worse for the company,” lawyer for Yukos shareholders Robert Amsterdam told Channel 4 News in 2004.

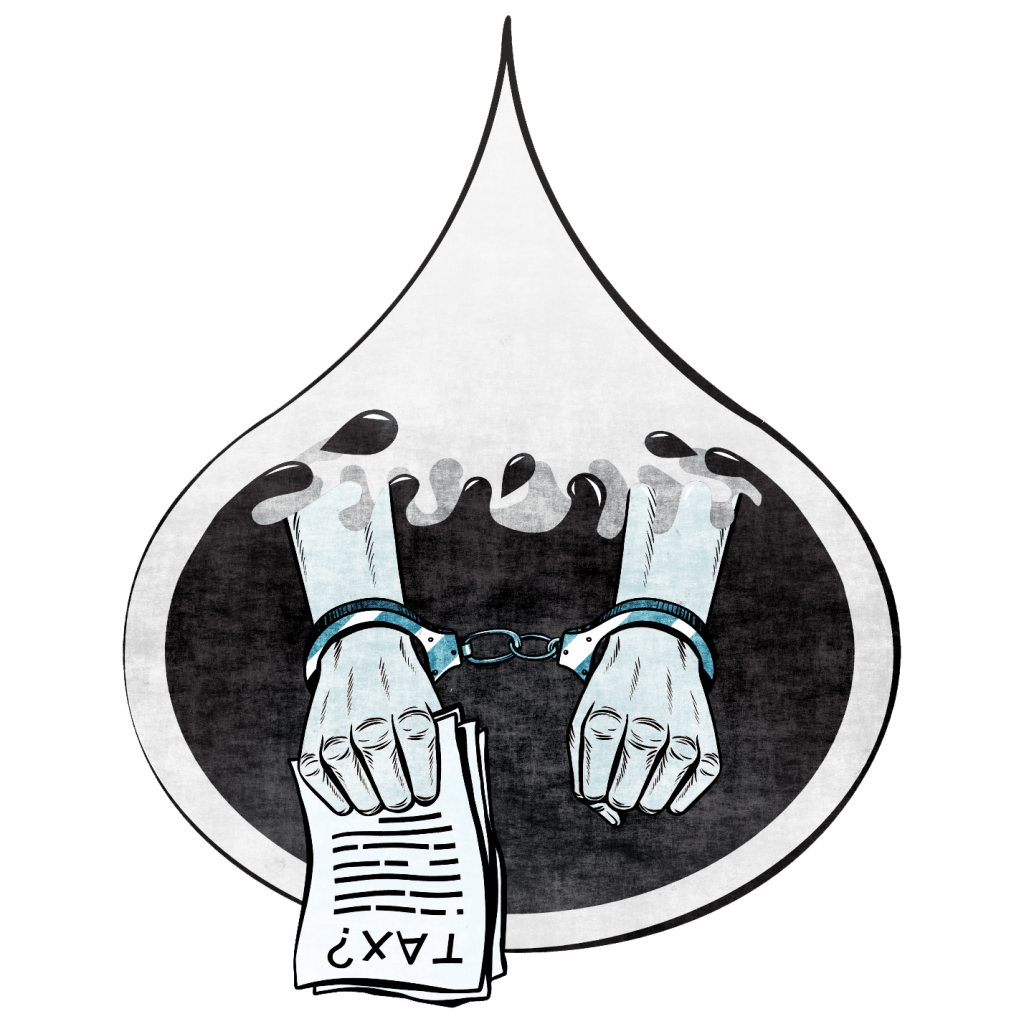

Curtis understood Yukos’ elaborate offshore structures and was said to keep a lot of the information in his head as Yukos tried to stay one step ahead of the Russian government.

Who would run the beleaguered Yukos oil empire? Khodorkovsky had been arrested at gunpoint and thrown in jail a few months earlier, and now Curtis had just fallen out of the sky. In the vacuum, one man stepped out of the shadows and offered to fill Curtis’ shoes.

It was an ambitious – and risky – undertaking in the fraught and suspicious atmosphere at that time. But the dapper Englishman volunteered his services.

Outside the world of finance, few had ever heard the name, Christopher Samuelson. He has been described as a “company administrator”, “fiduciary”, “trust manager”, as well as “money manager”, “businessman”, and “financier”.

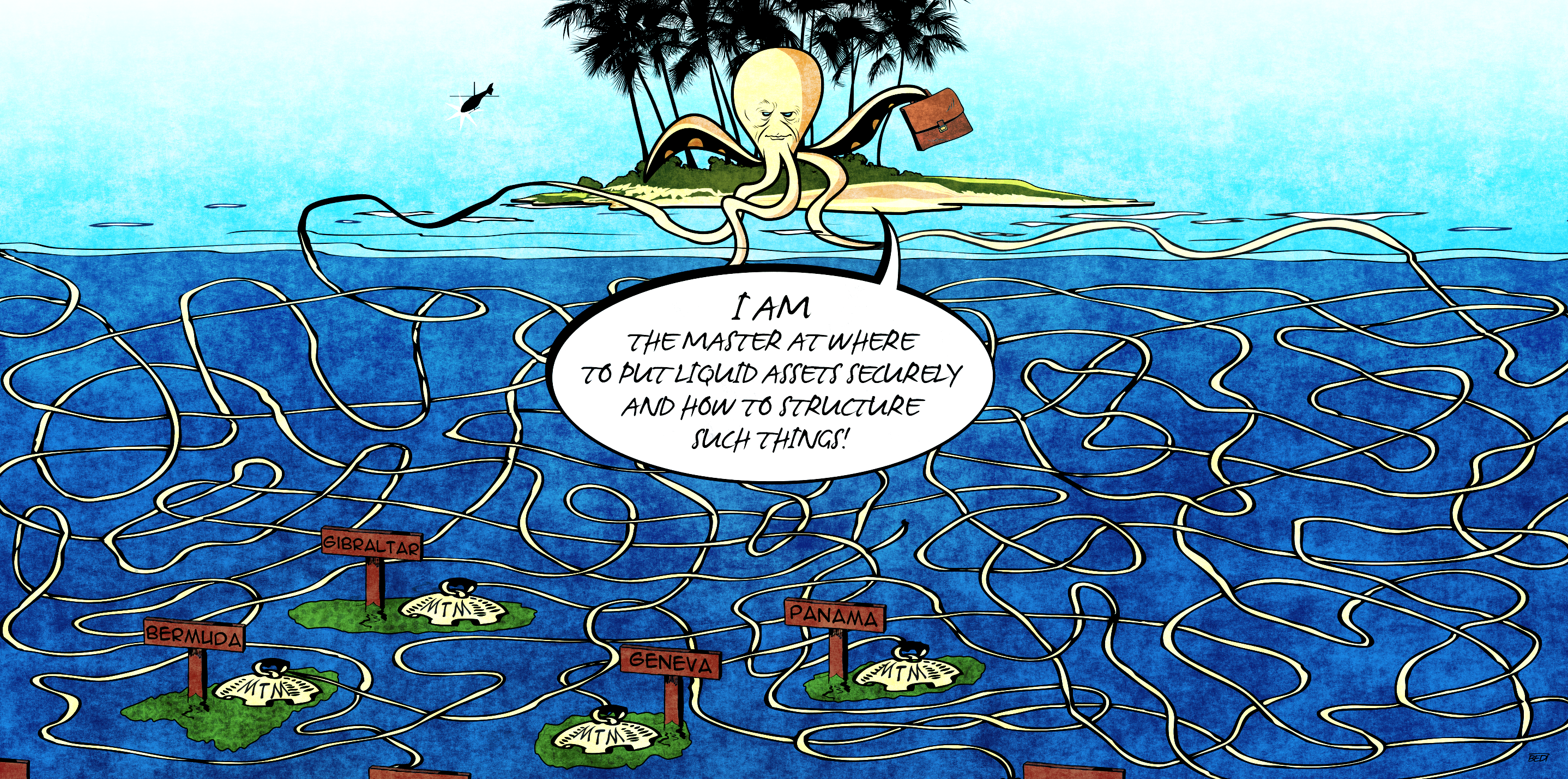

But to really understand what Samuelson was good at, you need to add the word “offshore” to those titles. Offshore is shorthand for secretive tax havens where billions of dollars – legitimate or otherwise – are stashed in banks, away from the prying eyes of taxmen, creditors and spouses.

“He’s a very pleasant, charming man, there’s no doubt about it. He’s good-looking, and he’s got a very easy grace to him… one of those guys who gets on with everybody,” said a source, who used to do work for Samuelson. “He hobnobs with some of the wealthiest people on the planet, and some of them are not particularly nice.”

From his bases in Bermuda, Geneva, and Gibraltar, Samuelson ran Valmet, one of the biggest offshore trust companies in the world and starting in the late 1980s, he nurtured a newly discovered rich seam of wealth: the former Soviet Union.

His links to the world’s richest would soon include “Godfather of the Kremlin” Boris Berezovsky; Berezovsky’s partner, the white-moustachioed Georgian oligarch Arkady Patarkatsishvili (known as “Badri”); oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky; banker Vitaly Malkin, one of the top oligarchs of the Yeltsin era; Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich; and Boris Zingarevich, the pulp and paper billionaire.

“He has access to the most incredible people: very wealthy, powerful people,” said the former associate.

Samuelson and Valmet, later known as Mutual Trust Management (MTM), set up and managed offshore trusts, companies and bank accounts for oligarchs and their businesses. Critics said the money was siphoned out of Russia, that it was capital flight that cost the Russian treasury billions and leeched from the state. Valmet would say the arrangements were above-board.

In meetings between Samuelson and undercover reporters from Al Jazeera’s I-Unit looking to “buy” a football club for their fictitious Chinese boss, the money manager was expansive about his business dealings with Russia.

In the covert recordings in plush hotels across London, the always impeccably dressed Samuelson spoke not only about football and the “sale” being discussed, but also about his decades-long relationships in Russia.

He spoke of travelling to Moscow more than 500 times, of how he even knows Vladimir Putin. How well he knows him, he did not explain, but Samuelson’s emails, seen by the I-Unit and disclosed during litigation, appear to show he was able to get meetings in the hard-to-access sanctuary inside the Kremlin.

Yet his involvement with Russia attracted the attention of investigators, who suspected him of leading a group involved in money laundering and corrupt practices, spawning investigations across Europe.

As Stephen Curtis’ helicopter plunged through cloud and drizzle into Dorset’s lush pastureland, Christopher Samuelson was island-hopping across the Caribbean’s tax shelters, on business in Antigua and the British Virgin Islands. He had spoken with Curtis just two days before, one of many conversations during the preceding months.

With the crisis precipitated by his friend’s death, the action was now miles away, back in London. Samuelson – described by the former associate as an “obsessive” workaholic who would chase even “whacky” opportunities – was soon in town, with a plan.

Khodorkovsky’s personal lawyer, Anton Drel, had stepped in to manage the emergency, so Samuelson typed out a letter understood to have been delivered through trusted intermediaries, by hand, to Mr Drel.

In his “letter to Anton”, the money manager made a pitch to replace Curtis as head of Menatep.

“Stephen was a close friend. Stephen’s tragic death has dealt an additional blow to our mutual client’s business and leaves a large vacuum,” Samuelson wrote to Drel.

“It has been suggested to me … that I would be an ideal choice to at least partly play Stephen’s role. I am ready to help in this matter,” he continued. “I am probably the nearest thing to Stephen and in fact, he and I often discussed strategy etc.”

Among his proposals, Samuelson said he could call on people in Houston, Texas, with influence in the White House, then occupied by US President George W Bush, to help Yukos. He also mentioned his links – through a prominent Gibraltar lawyer he had known for a long time – who could reach out to Ariel Sharon, the Israeli prime minister at the time, for help.

Samuelson went on to tell Drel that the previous autumn he had “discovered the location of the liquid assets of the holding company” during a meeting with the Menatep team in London and “insisted very loudly that it was imperative to move these at once” because of the threat of an imminent freezing order by the Russians.

In playing the game of cat and mouse between Yukos and Russian investigators, Samuelson told the Russian lawyer he had “inside sources in many corners” and was “monitoring actions and requests emanating from Moscow closely every day”.

“I am the master at where to put liquid assets securely (and how to structure such things),” he said.

Drel’s short visit to London the month after Curtis’ death was a whirlwind of meetings with lawyers, company officials and lobbyists. Yet according to documents seen by the I-Unit, Drel still found time to schedule a meeting with Samuelson on April 28. What became of Samuelson’s offer to step up amidst the chaos is not known, nor of his plans to solve some of Yukos’ challenges.

Samuelson later claimed to undercover reporters from the I-Unit that he had warned Khodorkovsky about the risk of arrest he faced over his fight with Putin.

“I told him it was going to happen; he didn’t want to listen. They [the Russians] didn’t want to arrest him. They wanted him to leave, but he decided to stay. So, they arrested him, and they convicted him of something he never did. They said it was tax evasion. Bulls**t, he was the one person who had paid his taxes.”

Khodorkovsky was tried, convicted and jailed. The Russian state effectively seized Yukos in a barely disguised raid.

So how did Samuelson know so much? How did he come to sit at the top table of oligarchs and power? To hear him tell his story in the I-Unit’s recorded interviews is to hear something of a maestro at work.

“He is a man in the shadows,” said the former business associate. “He keeps a low profile, which is one reason why he’s so successful. He plays shell games with companies, labyrinthine, complicated offshore companies… And you can never actually find out who the directors are. And that’s the whole point. Because the root of the money is what he’s protecting.”

In 1988, Valmet’s Paris office had a “walk-in”. A Russian businessman asked Samuelson’s partner at the firm whether they would be interested in financing a Moscow circus tour in the West, Catherine Belton, respected author and Russia specialist, wrote in a 2005 profile of Valmet’s role in Russia.

The Paris office director thought it must be a joke but it was the beginning of Valmet’s entry into the Soviet Union. Later, the walk-in phoned to say there were some young people in Moscow trying to start a bank; he wanted to introduce them to Valmet.

Three years later, in 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed, all was chaos and the biggest asset grab in history was on. By then Valmet had joined with Riggs Bank, an illustrious US bank, to seek out opportunities in the former Soviet bloc. While other capitalists were scrambling to find out who to call and partner up with, Valmet already had a client in Mikhail Khodorkovsky and his partners and had been working with the flannel-shirted future oligarch for more than two years.

In 1991, Platon Lebedev, Menatep’s financial director, told a reporter from the Christian Science Monitor that Riggs [meaning Riggs-Valmet] were “our teachers”.

Of Samuelson and his Valmet partners, Menatep shareholder Mikhail Brudno told then-Moscow-based Belton: “They taught us a great deal. They taught us about the principles of organising business: from both the financial and the business sides. We didn’t know anything. Until we met, we couldn’t even imagine how these business processes were built.” It was a good foot in the door for Riggs-Valmet: Menatep’s founders would become billionaires and go on to buy Yukos.

They were not Samuelson’s only Russian clients.

Samuelson claimed to undercover reporters from the I-Unit that he helped oligarch Roman Abramovich, the Chelsea football club owner, get his start in business. “I met Roman Abramovich in Moscow when a million dollars was a lot of money … Roman became a client.” Abramovich has denied having a personal relationship with Samuelson.

Even bigger and more controversial clients beckoned. In 2000, Samuelson told colleagues in a somewhat breathless note: “Our new clients are Boris Berezovsky and Arkady Patarkatsishvilli [sic]. …” The two oligarchs, close business partners who would soon fall foul of what Samuelson has called “regime change” under President Putin, who had replaced Boris Yeltsin.

He added that the two businessmen owned Russia’s fourth-biggest oil company and two-thirds of Russia’s aluminium smelters. They had “political clout… I cannot see any reason to refuse accepting BB and AP as clients.”

Badri, whose underworld name was allegedly “Badar”, was suspected – by government officials, due-diligence professionals, and experts – of being close to organised crime, particularly in Georgia where he was linked to a so-called “thief-in-law” (a major Russian criminal). Badri become Samuelson’s client and Samuelson became Badri’s personal trustee for the oligarch’s main offshore trust. The trust held hundreds of millions in assets and was a reflection of Badri’s confidence in Samuelson.

Samuelson rattled through the complex offshore structures he envisioned creating for the two men. “Other assets that we have to deal with include cars, planes (costing $70m), yachts (two presently worth about $40m), holdings in other businesses, other properties, trusts …”

The set-up fees for the first year alone, he added, were $1.6m. Valmet was doing well. And so was Samuelson. That same year, 2000, according to an internal company review, Samuelson’s salary alone was just under $300,000.

His proximity to oligarchs, and his financial dealings captured the attention of officers at an elite police agency that would focus increasingly on Samuelson, as well as Stephen Curtis’ oddly timed death in the helicopter crash.

In August 2005, the year after Curtis’ death, Dutch financial law enforcement agency FIOD-ECD raided the Dutch office of Samuelson’s firm, Mutual Trust – Valmet’s successor – carrying away boxes of documents. An adviser to Boris Berezovsky complained that while Samuelson had proved very expensive in setting up offshore structures that would frustrate inquisitive investigators, he had, ironically, kept all the documentation in one place only for it to be seized by authorities, thereby blowing the very secrecy the structures were meant to protect.

Two FIOD agents, in particular, doggedly pursued Samuelson in an investigation that lasted years, following the threads of the corporate webs spun by the trust manager. Later, in a letter sent in 2008 to a London financial investigator – and seen by the I-Unit – the FIOD agents asked: “Are there any notes made by Curtis… showing the information he possibly gave to the NCIS, especially relating to Samuelson?” The Dutch agents wanted to know if Curtis had disclosed to police any secrets about his friend Samuelson, his companies or his oligarch clients.

By 2005, Samuelson – the man with “inside sources in many corners” knew Dutch detectives were investigating him and his company: according to a previously confidential FIOD-ECD legal document, written in 2005 and obtained by the I-Unit, they suspected Samuelson was the “de facto” leader of an international organisation involved in money laundering and corruption.

Warning lights were flashing as investigations popped up across Europe. The I-Unit has seen heated emails Samuelson sent to a colleague in late 2006, spelling out impending dangers: “you and me are under suspicions [sic] of laundering money on behalf of AP [Arkadi Patarkatsishvili]”.

“You already have investigations by the Dutch, Spanish, Germans and French,” Samuelson said. He complained about the spiralling costs, stress, and unpaid bills. “AP and BB [Boris Berezovsky] are targets of investigators in the Netherlands and France, and those investigations are active and the investigators have obtained the help of the Germans and Spanish.”

Samuelson worried the US and UK might take an interest. In the emails to the same colleague, he mentioned, “the Netherlands and subsidiary Swiss investigations”, meaning the FIOD agents who asked their Swiss counterparts to raid Samuelson’s Swiss office, seize documents and interview him.

In a glimpse into Samuelson’s usually cloistered world, he added that his other clients were angry because he could not complete their work. Dutch investigators had taken “all our files” and not returned them. Samuelson underlined the risks: “The Netherlands case highlights the dangers of having clients with political exposure and why we charge appropriate trust fees.”

Dutch secrecy laws meant that little of this investigation became public, bar fleeting references in legal papers in other cases. However, Samuelson claimed the Dutch prosecutor dropped the case and “all claims against Mutual Trust Netherlands and its directors including me”. In a memo seen by the I-Unit, he mentioned he had a letter from his lawyers, Simmonds and Simmonds, confirming the case had been dropped.

Samuelson, the Teflon fiduciary, escaped the Dutch authorities but his friends, associates and clients working in and out of Russia were not so fortunate.

First, his friend and business associate Stephen Curtis had died in a crash doubts still lingered about. An inquest concluded it was an accident. A British Home Office review did not conclude foul play. But Boris Berezovsky remained suspicious, as did many others.

Then Khodorkovsky – Samuelson’s former client who he allegedly warned to get out of Russia – spent 10 years in a Siberian prison. He is out now, living in Europe, and is a vocal critic of Putin.

In 2006, another client, Berezovsky’s security adviser, Alexander Litvinenko, was murdered in London using polonium.

Then in 2008, Patarkatsishvili died at home in Surrey. Questions arose over his death – which also unleashed a bitter struggle over his fortune.

Then in 2013, Berezovsky was found hanged at home. At the inquest, the coroner returned an open verdict saying he could not prove either way whether the oligarch had died by suicide or been murdered.

In 2018, Berezovsky’s close associate Nikolai Glushkov was found strangled at home.

The coincidences are chilling. If there is a Russian “ring of death” – a trail of assassinations and suspicious deaths tracing back to Moscow – Samuelson seems to have a ringside seat.

But Samuelson is still doing the deals. Salvaging gold-laden shipwrecks off Ireland, drumming up investments in Africa, hobnobbing with senior officials in different countries – and pursuing his love of football, helping rich foreigners buy English football clubs.

The Zingarevich family, old Russian clients of his, tried to buy Everton football club in 2004 but the deal fell through after Zingarevich’s identity was leaked to a Sunday paper. In 2012, hebought Reading instead in a deal where Samuelson joined the club’s board.

In keeping with the times, Samuelson turned towards a new reservoir of billionaires: China.

First, he helped billionaire Chinese businessman Tony Xia buy England’s Aston Villa FC in 2015.

Then along came Bill – another “walk-in” – and his courteous, dependable assistant Angie. And the whole circus started again … it just so happened that they were undercover reporters from Al Jazeera’s I-Unit this time.

Christopher Samuelson’s lawyers told the I-Unit that he is an experienced businessman who built an established reputation in the financial trusts and football industries and would never take part in any deal where criminality was involved. They said that Samuelson had never been told that our fictitious Chinese investor had a criminal conviction for money laundering and bribery and that he would have ended discussions immediately had he been told of any criminality or money laundering.

A spokesman for Mikhail Khodorkovsky denied that Samuelson had advised him and said that it was “highly likely” that he had never met Samuelson.

Lawyers for Roman Abramovich described Samuelson’s claims about him as “false” and denied that he’d had any business relationship with Samuelson.