Long Read

Cyprus’s dirty secrets

Al Jazeera’s I-Unit looks at what a leak of confidential documents tells us about Cyprus’ citizenship by investment scheme.

26 Aug 2020 | 20 min read

It was a typically chilly December morning in the Vietnamese capital. A phalanx of press had gathered outside the formidable Hanoi People’s Court; a grand, white, pillared structure that was the venue for the trials of senior Communist Party officials accused of malfeasance, with all the proceedings televised.

It looked like 66-year-old former Minister of Information Nguyen Bac Son might become the latest to be ensnared in the government’s sweeping anti-corruption campaign, and the press was watching as he was ushered into the court by family.

Son was a powerful figure in the Vietnamese government from 2011 to 2016. Late last year, after a two-week trial, he was jailed for life for receiving a $3m bribe in a deal involving state-owned telecoms firm MobiFone and private pay television firm Audio Visual Global JSC (AVG). He was spared the death penalty only because his family paid the money back to the state.

Earlier, a quieter entrance had been made by the man who gave the bribe, former AVG Chairman Pham Nhat Vu. Bespectacled and balding, he gripped a microphone and spoke intently, as if from a script. Prosecutors said Vu had actively cooperated with the authorities in the investigation, and he duly confirmed that he had paid $3m to Son.

Vu cut an unimpressive figure in court. He did not look like someone who was part of a global elite and could, if not incarcerated, travel and settle anywhere he chose.

But Vu has powerful backers. His brother Pham Nhat Vuong is the richest man in Vietnam. Letters appealing for clemency for Vu were sent by the powerful Buddhist Sangha of Vietnam, the Vietnamese Red Cross Society and the Russian ambassador. His sentence was just three years in jail.

Vu came to the attention of Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit for a different reason altogether. Shortly before his court appearance, he had been granted a passport by the Republic of Cyprus.

A ‘golden’ passport

Pham Nhat Vu is one of thousands who paid to receive Cypriot citizenship under a citizenship-by-investment scheme, and features on the list of those revealed in The Cyprus Papers, a huge leak of official documents obtained by the Investigative Unit.

The Cypriot government has long considered what is today known as the Cyprus Investment Programme (CIP) to be a major revenue stream – some estimates say it has generated about $8bn – and it is no surprise that it was ramped up in 2013 following the worst financial crisis in the Mediterranean country’s history.

For those with money to spare, the advantages that come with a “golden” Cypriot passport are clear: the ability to deposit their money in European bank accounts and live, work and travel freely not only in Cyprus, but across all 27 European Union nations, and visa-free travel to 176 countries – all at the “reasonable” price of a minimum investment of about $2.5m, most of which must be spent on real estate.

The Cyprus Papers

The Investigative Unit has researched some 2,500 people named in The Cyprus Papers who appear in more than 1,400 applications for citizenship, as principle applicants or family members. Individuals have been named only when there is clear evidence that the person has been involved in wrongdoing or when he or she is a public official who would no longer be eligible for citizenship under a new set of rules Cyprus introduced in 2019.

The largest number of applicants – 1,000 – is from Russia, followed by 500 Chinese nationals, just over 100 from Ukraine, and 350 from the Middle East.

They represent a range of ages and professions but, in every case, they have acquired substantial wealth, sometimes by questionable means.

What stood out in the investigation is that Pham Nhat Vu is among dozens of applicants who would not be accepted had they applied for passports today and had their applications received appropriate scrutiny.

The CIP was introduced in 2016 and replaced an earlier citizenship-by-investment scheme. It included new financial criteria for those wishing to obtain citizenship, lowering the required investment by more than $1m. Like its predecessor, it required applicants to possess a “clean criminal record” but failed to define what that meant.200823213842462

It appeared to not exclude those involved in criminal proceedings or under investigation, and many of the applicants appearing in The Cyprus Papers had applied as they were about to be convicted of a crime.

The Cypriot government is required by its own regulations to conduct follow-up checks in the Europol and Interpol databases. In practice, however, it was up to the applicants themselves to submit their own background checks from authorities in their home nations. The rejection rate was surprisingly low, just two percent of applications between 2013 and 2018

One individual with a conviction for extortion 16 years earlier was classified as having a “clean criminal record”. This poses the question of whether the criminal record of a man who is now part of Russian high society was overlooked – or whether it was considered expunged.

Businessmen, politicians, billionaires

On a cold December evening in 2015, St Petersburg’s fashionable elite had gathered for a party. Among the glittering guests were famous television host Ivan Urgant and socialite Ksenia Sobchak, daughter of the first democratically elected mayor of the city and his wife, a member of the Russian Senate.

They were there to celebrate the birthday of a nine-year-old boy, the youngest son of Ali Beglov, who spent $500,000 on the bash.

Beglov, a burly man with tightly cropped hair, is also known as “Alik Tartarin”, a moniker from his days in the St Petersburg underworld. He had served a two-year sentence in jail from 1990 to 1992 for extortion.

The conviction did not prevent Beglov from acquiring a Cypriot passport, nor did it preclude him from ascending to the highest circles of power in Russia.

From 1999 to 2016, Beglov was general director of a subsidiary of Russia’s second-largest oil and gas corporation, Lukoil, which manages oil storage units in 35 ports across Russia and abroad, generating net profits of one billion roubles a year ($13.2m).

Months before Beglov’s lavish party for his nine-year-old, a newly formed dairy company run by his older son set up office in the regional headquarters of Lukoil on the riverfront in St Petersburg. A year later, the company was already supplying dairy products to Russia’s Constitutional Court, the Federal Security Service (FSB), the State Duma, and the Federation Council.

In neighbouring Ukraine, where the notoriously corrupt presidency of Viktor Yanukovich was overthrown in the Euromaidan revolution of 2014, the elite were also eager to get Cypriot passports.

Among them was Mykola Zlochevsky, who has been accused of abusing his position as Yanukovich’s minister of ecology and natural resources to benefit his energy company, Burisma Holdings – based in Kyiv but notably registered in Cyprus – to gain preferential access to Ukrainian natural-resource extraction licenses.

Burisma made headlines in the United States after it emerged that former Vice President Joe Biden’s son, Hunter Biden, had joined its board of directors while his father was in charge of the US’s Ukraine policy.

Zlochevsky has been under investigation for corruption since leaving his ministerial post in 2012. More recently, he was charged with bribery after anti-corruption officers seized $5m in cash, allegedly destined to make the investigators drop their inquiries into Burisma. He acquired a Cypriot passport on December 1, 2017, and now reportedly lives in Monaco.

Even before The Cyprus Papers, much has been written about Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs who have bought Cypriot citizenship, including Oleg Deripaska, a billionaire businessman close to President Vladimir Putin.

The successful applicants also include one of the world’s most wanted fugitives, Low Taek Jho, popularly known as Jho Low and allegedly the mastermind behind a $700m fraud scandal that brought down former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak.

Perhaps in response to such reports, in 2019 the Cypriot interior ministry made a series of announcements, including the revocation of 29 passports that had been granted in error and the strengthening of the eligibility criteria for future applicants.

Anyone deemed to be a politically exposed person (PEP) – an official in a high-profile position in government or state-owned enterprises – would in the future be prohibited from becoming a Cypriot citizen for at least five years after leaving the post, as would his or her family members and business associates.

Corruption investigators claim that PEPs are much more likely to be involved in corrupt activities because of their access to state funds.

The law also clarifies restrictions on applicants associated with sanctioned entities and those under investigation or facing criminal charges before a trial.

The ‘Kremlin’s Bank’ and global PEPs

In the aftermath of Russia’s takeover of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, the US and the EU placed sanctions on key sectors of the Russian economy, impacting VTB Bank. For years, VTB had been a linchpin in Moscow’s projection of economic power, from pumping investments into the former Communist-bloc and new EU member, Bulgaria, to bankrolling the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games. It became known as the “Kremlin’s bank”.

Three of VTB’s leading executives invested in neighbouring properties at the Coral Seas Villas development near Paphos, a seafront resort in Cyprus. Alexei Yakovitsky, CEO of VTB Capital, Victoria Vanurina, member of the VTB Bank Management Board, and Vitaly Buzoverya, senior vice president of VTB Bank, were all approved for Cypriot citizenship along with their spouses.

Data gathered by anti-corruption NGO Global Witness shows how, between 2007 and 2016, Cyprus was the number-one destination for outward foreign direct investment by Russian residents – otherwise known as capital flight – estimated at nearly $130m. Although there is no suggestion that this money is being used for criminal purposes, there is growing evidence that Cyprus has become a favoured destination for Russians seeking to launder the proceeds of ill-gotten gains.200818112722072

Granting citizenship to applicants who are PEPs has been a contentious issue for the EU, and its rules severely restrict PEPs from acquiring an EU passport. It took until the summer of 2019 for Cyprus to fall in line with these rules, but not before many PEPs took full advantage of the Cypriot programme.

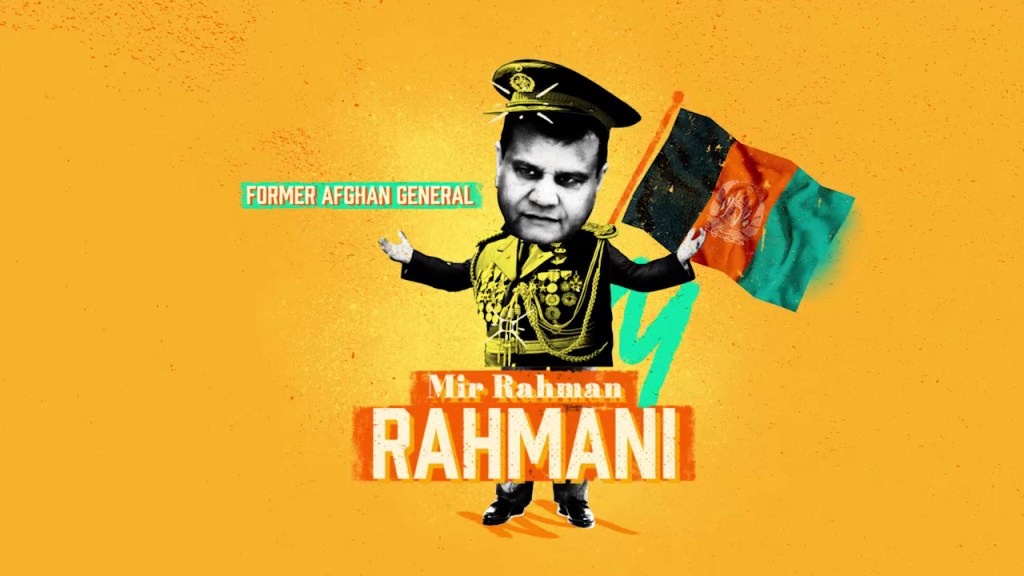

Speaker of the lower house of the National Assembly of Afghanistan Mir Rahman Rahmani is a high-level PEP. Before entering politics, Rahmani built his business empire supplying the occupying US military in Afghanistan with fuel and security services. His approved application states that his wife and three daughters are also citizens of Saint Kitts and Nevis, another country with a citizenship-by-investment programme. His son, Haji Ajmal Rahmani, a politician representing the capital city, Kabul, also sought Cypriot citizenship.

The Rahmani Group has interests not only in Afghanistan but also in the Gulf and Europe. As far as corruption experts are concerned, the Rahmani father and son are potentially in a position to steer policy in a way that would lead to their personal enrichment. And a Cypriot passport would allow them to deposit their wealth in a European bank account, far from scrutiny.

The Cypriot government’s due diligence checks should also have spotted Vladimir Khristenko, a PEP through his father, Viktor Khristenko and his stepmother, Tatyana Golikova. Both have held a number of leading political positions as well as serving as deputy prime ministers of Russia, while Viktor has served twice as minister of industry. Golikova, once described in the Russian media as “one of the most odious deputy prime ministers of the Russian Federation”, has served as minister of health and as an aide to Putin.

The couple declared an annual income in 2017 of more than $1m, although their combined net worth is estimated to be far greater, not least due to significant stakes in three luxury golf resorts with a combined value of $360m. According to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, an investigative reporting platform, “It’s not clear from their public income declarations how Khristenko and his wife Golikova could have afforded such valuable assets.”

In 2006, Vladimir, aged 25, became chairman of the supervisory board of a Czech subsidiary of the Chelyabinsk Pipe Rolling Plant group. He now runs pharmaceutical company Nanolek – owned by a Cypriot entity – which has reportedly been developing a vaccine for COVID-19, as well as producing hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug that has been promoted by some to treat COVID-19 despite its unproven efficacy in combatting the coronavirus.

The leak obtained by Al Jazeera, spanning a two-year period between 2017 and 2019, highlights a systemic failure of the CIP. Regulations were not strictly enforced and ineligible applicants continue to be approved well after the government supposedly tightened the rules in February 2019.

Money-go-round

After months of delay, the Cypriot parliament passed a law in July 2020 allowing the government to revoke citizenship from anyone sentenced for a serious crime, facing international sanctions or placed on an international wanted list after they became a citizen.

Cyprus’s Minister of Interior Nicos Nouris, who is in charge of the CIP, told Al Jazeera that no citizenship had been granted in violation of the regulations in force at the time. Cyprus functions, he said, as an EU member state with absolute transparency.

Despite attempts to close loopholes, several NGOs, members of the European Parliament and some opposition figures in Cyprus are calling for the programme to be scrapped entirely. Opposition politician Irene Charalambides says, “[The government] is putting the European Union in danger. They are opening the gates of the European Union with the passports they are selling.”

While Cyprus’s reputation has been damaged by the revelations about the programme, it is not the only victim in the money-go-round of purchasing citizenships. In many cases, the funds invested on the golden beaches of Larnaca and Paphos were stolen from the Russian, Ukrainian and Chinese people. As corruption undermines the standing of an EU member state, it also undermines the development of civil society in the countries where the money was sourced.

The passports may be Cypriot, but the anonymously registered companies are in Jersey, the bank accounts often in London. The yachts are docked in the Cote d’Azur and the people suffering are in Kabul, Khabarovsk and Kyiv.