Article

36 July: Hasina’s Last Days

The student uprising in Bangladesh that toppled a government in power for 15 years was a remarkable story of courage and sacrifice in the face of extreme violence. More than one thousand four hundred young protestors were shot dead, over twenty thousand were badly injured and many with bullet wounds over three bloody, momentous weeks in July and August 2024.

24 Jul 2025

By Will Thorne

Nothing about the death of Abu Sayed was normal and nothing about it was final. As Dr. Rajibul Islam re-wrote his autopsy report under the watchful gaze of the most feared and powerful security agencies in Bangladesh, he wondered how it would all end.

Crammed into the Vice Principal’s office at Rangpur Medical College on that day were officers from Directorate of Forces Intelligence, National Security Intelligence, local police, counter terrorism, special branch and the head of the local medical association.

For good measure Dr. Islam had been told in very clear terms that the prime minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, also had a strong interest in this post-mortem.

The room was full for one reason, to make sure that the head of medical forensics at Rangpur hospital filed an autopsy report that would conclude that a local male student had died from a blow to the head.

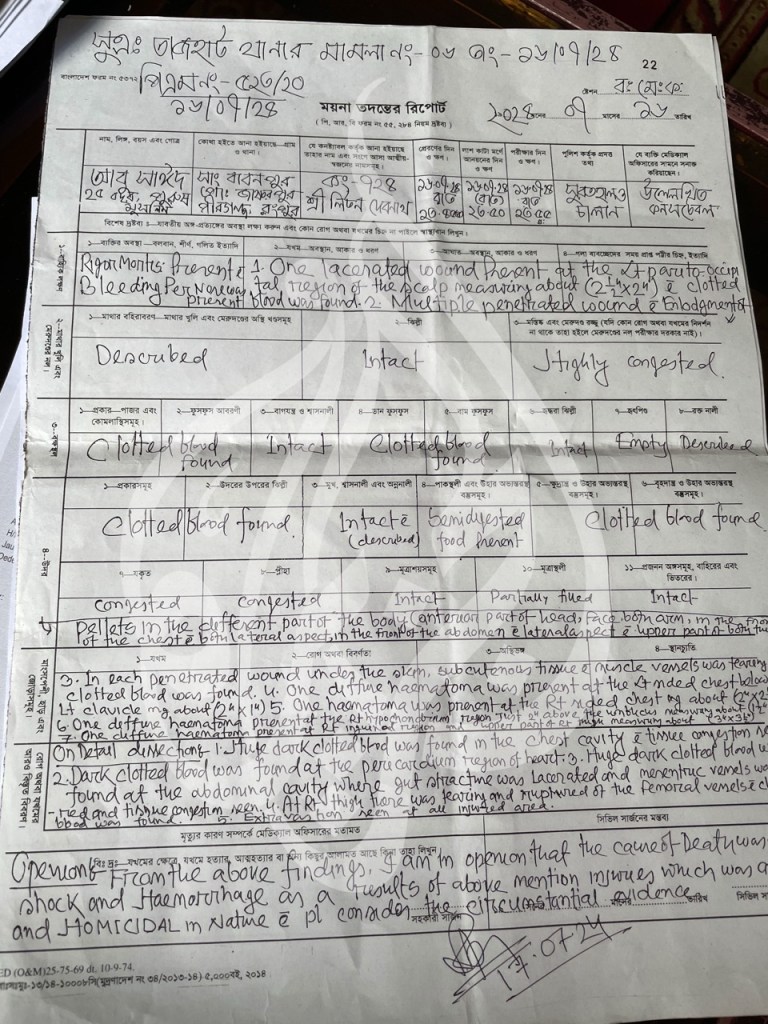

This was the fifth time Dr. Islam had written and submitted his post-mortem report to the police, four previous attempts had all been rejected as the forensic expert kept arriving at the same inescapable conclusion. That twenty-four-year-old Abu Sayed had been shot several times at close range by police and had died from internal haemorrhaging.

“No matter how many times I wrote it, they were not satisfied…. the police truly realized the seriousness of the matter since it was an extrajudicial killing.” Said Dr. Islam.

Perhaps in different times and under different circumstances the police killing of a student could have been covered up. In a different time, the government of Sheikh Hasina held a powerful grip on all the institutions of the state and exercised near total control over the press, but this was different.

On the mortuary examination table was a young man called Abu Sayed his body riddled with shotgun pellets. He died on July 16th, 2024 – his death was streamed live on social media and quickly went viral in Bangladesh and around the world.

There was little room for doubt about the cause of death and no time for the government to control the narrative. It was out there, the shocking record of a man’s last minutes alive being shared and played over and over again.

If this was no ordinary post-mortem it was no ordinary death either. On that day Abu Sayed had been protesting outside Begum Rokeya University in the provincial city of Rangpur two hundred kilometres north of the capital Dhaka.

He’d taken to the streets along with thousands of other students around the country to protest against a government policy, called the quota system, that reserved thirty percent of civil service jobs for the families of those who had fought in the country’s war of liberation in 1971, known as freedom fighters.

This valuable privilege, which was extended to the grandchildren of war veterans, had long been a major source of frustration for students who faced huge challenges in finding a job. Following public protests, it was suspended in 2018 but was re-instated in June 2024 despite the country facing serious unemployment.

The protestors were campaigning to reform a system that tended to favour supporters of Sheikh Hasina’s ruling Awami League party. It started peacefully in Dhaka in early June with highly disruptive street blockades.

An increasingly frustrated prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, used a televised press conference on July 14th where she used the word Razazkars, a highly insulting term for those who collaborated with the enemy, Pakistan, during the war of liberation fifty years ago.

The students felt she had branded them all as traitors. Her comments sparked a new and violent stage of the protests as the ruling party’s youth wing, known as the Chhatra League, launched brutal attacks on student protestors in Dhaka.

Phone videos of the violence spread fast on social media and soon campuses up and down the country, like Rangpur’s Begum Rokeya University, joined the protests in solidarity. Now students, like Abu Sayed, were protesting about two things: the quota system and the use of state violence to stop the protests.

The government now faced a movement that was young, angry and highly skilled at communicating and organising on social media. Sheikh Hasina often boasted how she’d built digital Bangladesh; she was about to find out how quickly the digital realm could shift the balance of power.

A young man from Rangpur who’d watched the bloody protests in Dhaka on social media was Tawhidul Haque Siam, a student journalist who was determined to cover a demonstration at his campus.

Speaking from the ruined interior of Gananbhaban, the prime minister’s official residence, for long the seat and symbol of Sheikh Hasina’s political dynasty, Saim told Al Jazeera about that fateful day.

“…when we arrived at the first gate of the campus, our goal was to cover the news — to do journalism. As soon as we reached there, we saw a standoff between the police and students.”

“Abu Sayed wasn’t involved. He was standing in the middle of the two campus lanes, just observing everything.”

The violence quickly escalated as the police started to use tear gas, batons and then shotguns to disperse the protestors.

Throughout Siam kept filming on his mobile phone, sending pictures live along with a frantic commentary to his Facebook page, a dramatic and at times deeply disturbing record of events that was to provoke a national outcry.

In the course of several chaotic minutes of “live” broadcasting the young journalist intervened to stop Abu Sayed being badly beaten by five police men, shielding him from baton blows with his arms. Next, he filmed as a policeman aimed a revolver at Abu Sayed, the officer spots the camera and lowers his gun.

As students scattered Abu Sayed remained alone, before the police, he raised his arms and shouted “Shoot me. Shoot me.”

“His intention was to inspire courage in the frightened students. At that moment a policeman shot him…..the first bullet hit his stomach…a second struck his chest.” said Siam.

As the young man lay dying in the street Siam kept recording as he and others desperately tried to carry Abu Sayed to safety, still under heavy police fire.

“He couldn’t speak anymore, but his eyes still held a message. When I think about that moment, I become very emotional. His mouth may have had no words, but his eyes did. — there was a deep sense of sorrow in his eyes,” said Saim.

Within minutes pathologist Dr. Islam was getting phone calls, lots of them, from police and local officials.

“The police started contacting me right after Sayeed was shot, meaning after 3 pm”.

“And senior police officials started talking to me and they emphasized that since…. the whole world saw Sayeed being shot, I should quickly complete the post-mortem and dispose of the body, and they also told me to focus more on the fact that Sayeed had a head injury.”

Over the next 14 days the doctor Al Jazeera he’d had to withstand threats, bribes and intimidation to write a report that fitted with the police narrative – Abu Sayed had died from a head injury caused by protestors throwing rocks.

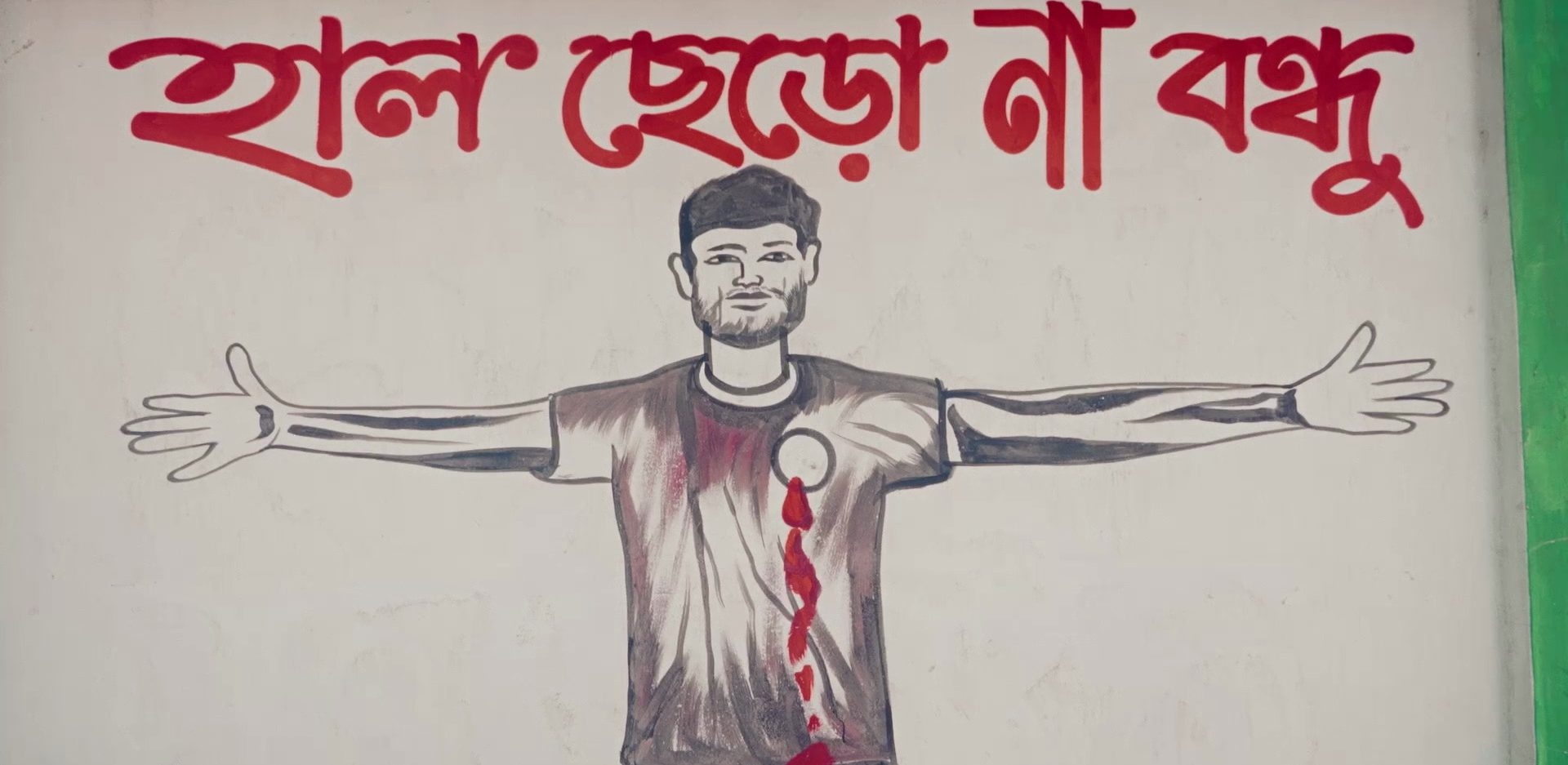

But in digital Bangladesh things were moving too fast. Abu Sayed’s image started appearing on walls and buildings throughout the country. His picture, standing defiant before armed police, his arms flung wide, became an icon of the uprising. He was one of the first protestors to die, there would be over fourteen hundred by the end, but his death had the biggest impact.

Student organiser Shadik Kayem explained.

“Abu Sayed’s martyrdom was a source of inspiration for us. The way he died, with his two arms outstretched as a martyr, each of us pledged to become an Abu Sayed”

A secret government initiative to negotiate with student leaders died along with Abu Sayed that day. A senior intelligence officer who had a back channel to student leaders told Al Jazeera;

“I talked to the students, they said after this video, after the death of this man, it is very difficult for us to sit with the government.”

Al Jazeera has obtained secret phone recordings of Sheikh Hasina and her most trusted allies which reveal how desperately the government wanted to contain the fallout from Abu Sayed’s killing.

The prime minister operated a deep surveillance network that recorded phone calls of opposition politicians, but also her own ministers and officials. Few it appears were above suspicion.

During the July uprisings Hasina shut down the internet and blocked social media sites like Facebook and WhatsApp to disrupt the protestors’ ability to organise and to stop damaging images of violence reaching the outside world.

But she’d set herself a trap. No longer able to use secure digital channels, Sheikh Hasina started to make calls on open phone lines, calls that were recorded by her spies.

Al Jazeera had the recordings analyzed by audio forensic experts to check for AI manipulation and the callers were identified by voice matching.

Al Jazeera obtained a recording of a call between her most trusted confidant and minister Salman F Rahman and the chief of police Chowdhury Abdullah Al-Mamun.

In the call the economy minister presses Al-Mamun for Abu Sayed’s post-mortem report.

Salman F Rahman: Hello. Okay, Mamun, (Chief of police) about that—Abu Sayed from Rangpur who died has his post-mortem been done? Have you received the report?

Police Chief: “We haven’t received it yet,sir.

Salman: Why haven’t you received it yet? Why is it taking so long?

Police Chief: Sir, that’s their matter. They haven’t given it to us yet sir. They haven’t given to us sir. They play hide and seek with us sir.

Even one of the most powerful figures in Hasina’s government using all its might could not obtain the pathologist’s report. Dr. Islam’s game of ‘hide and seek’ was frustrating the state’s efforts to tell a different story about Abu Sayed’s death.

Within 48 hours of his death street protests were raging across the country, slipping beyond the control of the Awami League government and their security chiefs.

Bangladesh had endured years of state corruption and harsh political repression against the backdrop of a worsening economy. Abu Sayed had become an icon of the uprising and the growing death toll among student protestors just added fuel to the fire.

The embattled leader took a greater role in directing her security forces, using over fifty mobile phones, but her calls were still recorded by her National Telecommunications Monitoring Centre. They revealed the ruthless measures she was prepared to take to confront the quota protests.

Two days after Abu Sayed’s death, Sheikh Hasina was recorded talking to her close relative, Sheikh Faisal Taposh, the powerful Mayor of Dhaka South who reported that demonstrators were moving towards an area of Dhaka. The prime minister says she’s ordered her feared paramilitary force, RAB, into action backed up by helicopters.

Taposh (Nephew): : Yes, then your instructions will be needed.

Sheikh Hasina: No, my instructions have already been given. I’ve issued an open order completely. Now they will use lethal weapons, shoot wherever they find them.

Taposh (Nephew): Yes.

Sheikh Hasina: That has been instructed, I have stopped them so far..I was thinking about the students’ safety.

Hospitals in the city started to report multiple incidents of protestors being shot from helicopters.

All the while senior intelligence officers were still trying to get hold of the potentially explosive autopsy report from Dr.Islam. Speaking anonymously out of fear for his safety one officer told Al Jazeera:

“I tried to collect (it) but actually doctors were reluctant to write the report. If it goes against the government, the government will catch hold of them. And if it goes against the students, students will attack their hospitals and others. So I sent my people, but doctors did not give me any (report), they said that they had (yet) to write (it).”

“Abu Sayed died with a video which has been viral in the entire world…. the government will be in real trouble now..” he said.

Despite the evidence, her intelligence chief said Sheikh Hasina continued to tell her inner circle that the student had died from a blow to the head and that his death had been engineered by protestors to inflame public opinion.

Back in Rangpur Dr. Islam was stalling government efforts to manipulate the report, asking him to remove any references to guns or shooting.

“Each time I mentioned in the report that Sayeed’s death was due to multiple pellet injuries and internal haemorrhage, from a shotgun injury or shotgun bullet, and that it was homicidal… the police didn’t like it. Because the police were getting into trouble, that the police shot him and killed him, it was an extrajudicial killing.”

“The situation was very bad at that time because the government was very aggressive and I am a government employee, anything could happen to me, and then the police kept pressuring me to give a report like theirs.”

The Bangladesh government even offered the doctor an all expenses paid holiday;

“They offered me to submit a report like theirs and then go to Thailand with my family. I said no, I won’t go. After that, they told me to go to Cox’s Bazar (beach resort) with my family for two weeks of vacation.”

Dr. Islam stood his ground, refused the bribe and did his best to submit a report that listed the critical injuries that led to Abu Sayed’s death, even if he had to remove any reference to a gun or shooting. He would not remove the word homicidal.

But Sheikh Hasina was not finished with Abu Sayed’s death just yet, there was one more attempt to salvage government credibility after his very public killing. The prime minister arranged for Abu Sayed’s relatives, along with the forty other families who’d lost children in the protests, to come to her official residence; it was to be filmed by state television.

Abu Sayed’s father Maqbul Hossain picks his way carefully through the broken glass strewn on the floor of Hasina’s ransacked reception room– he’s in the very room where they were paraded in front of the cameras as Sheikh Hasina gave each family money. Scrawled on several walls is his son’s name – Abu Sayed. Graffiti of the uprising.

“Seeing it feels like my son’s name has spread everywhere, and Hasina’s palace, which was decorated and adorned, has now been obliterated, vandalized, and now it looks like a ruined house, doesn’t it? That’s what I’m seeing now.”

Hossain remembers the day well.

“Hasina forced us to come to the Gonobhaban (prime minister’s official residence). All the administration officials came and said, “Car, accommodation, food, travel, everything is free, you must go.” Hasina was in power then, we couldn’t refuse to go…. we were forced to come.”

Abu Sayed’s sister, Sumi Khatun, recalled the events too.

“We had a fear inside, because Hasina was in power then, they had killed my brother…. We were afraid and they forced us.”

Abu Sayed’s family were the first in a line to be presented to the prime minister, while the cameras filmed she gave them money. Sumi Khatun described the scene.

“She (Hasina) said, “We will deliver justice to your brother after we investigate who killed him. I said, “It was shown in the video that the police shot him, what is there to investigate here?” Even then she said, “We will investigate and then do justice.”

“Coming here was a mistake….we understood that Hasina would say that Abu Sayed’s family has no regrets that their son died….that we had reached an agreement. We felt very bad” said Sumi.

This televised show of sympathy for the grieving families had little impact. The newspapers and TV screens were filled with pictures of the daily battles between protestors and police, nearly twenty thousand students were badly injured by the end, and many government buildings were damaged. Dozens of police officers and Awami League supporters also died.

The killing of Abu Sayed became a focal point for the protest movement. No amount of intimidation could suppress the anger that poured onto the streets of Bangladesh that July. Anger that eventually toppled a government and sent Sheikh Hasina fleeing into exile.

Staring at the ruined official residence, rooms where once Hasina held absolute power Sumi Khatun expressed hope that Abu Sayed’s death will bring lasting change.

“Our wish is that the next government that comes should be just and fair, not a dictatorial government, so that no mother’s lap is emptied for a just cause, no sister loses a brother…no one should have to sacrifice their life to achieve rights.”

In a statement to Al Jazeera, an Awami League spokesperson said Sheikh Hasina has never used the phrase, “lethal weapons”, and did not specifically authorise the security forces to use lethal force. The former prime minister also disputes the authenticity of the July 18th call.

On the death of Abu Sayed the statement added, “ the government’s resolve to look into potential misconduct by all parties engaged in violence, including the security forces, was genuine.”